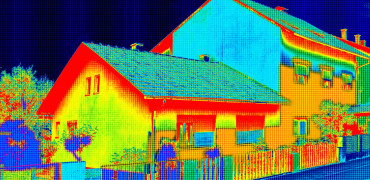

On the 22nd March 2021 Business secretary Kwasi Kwarteng and housing minister Chris Pincher announced that the government will allocate £562m to 200 separate local authorities to spend improving the UK’s least energy efficient and fuel-poor homes.

The scheme will see measures such as cavity wall, underfloor and loft insulation, and replacing gas boilers with low carbon alternatives like heat pumps, with solar panels also offered to many residents.

The funding comes after the government last year spent £50m on a pilot project to improve the energy efficiency of social housing stock.

MPs said the government urgently needed to develop a full national retrofit programme to upgrade 19 million UK homes, or risk failing to meet legally binding carbon reduction targets.

Whilst many industry experts don’t believe it will be enough given the scale of the issue, the funding will at least see improvements made to 50,000 homes and create 8,000 jobs.

We cannot meet climate objectives without major improvement in UK housing

Simply not enough

President of the RIBA, Alan Jones said he was pleased to see the government prioritising the improvements to homes of lower income people but said the policy “seriously underplays the scale of the problem” and was “simply not enough” funding.

“We need an adequately funded National Retrofit Strategy. The government must go further and faster to save our shameful housing stock.”

Launching the policy, Pincher said the investment would cut 70,000 tonnes of carbon emissions each year.

This is a bold aim, and undeniably a step in the right direction. However, could it be thrown off course by the current materials shortage?

Materials shortage

Lead times have lengthened for most products while materials firms are finding it difficult to build up stock levels as clients across the globe engage in a flurry of construction activity to prepare for the end of lockdown following vaccine rollouts.

Timber and roofing materials continue to be the worst affected products, with no improvements likely to be seen in timber supplies this year.

Very little timber is currently coming into the UK that is not already pre-sold, with global demand outstripping supply, while supplies of roofing products are not expected to improve until the second half of the year at the earliest.

Raw materials shortages and factory closures outside the UK are also hitting supplies of a range of key products including plastics, insulations, paints, packaging and adhesives.

Steel is also being hit by price hikes and longer delivery times with evidence suggesting shortages of some steel products may continue into the second half of the year, while pent-up demand for landscaping products may also lead to delays over the spring and summer.

The scale of the issue

Unfortunately, policy failings have made Britain’s housing stock a significant contributor to CO2 emissions.

On the whole, UK homes are not fit for the future. Greenhouse gas emission reductions from UK housing have stalled, and efforts to adapt the housing stock for higher temperatures, flooding and water scarcity are falling far behind the increase in risk from the changing climate.

We must make sure the 4m social homes and 25 million other existing homes across the UK are made low carbon, low-energy and resilient to a changing climate.

This is a UK infrastructure priority and should be supported as such by HM Treasury. Homes should use low-carbon sources of heating such as heat pumps and heat networks.

The uptake of energy efficiency measures such as loft and wall insulation must be increased.

At the same time, upgrades or repairs to homes should include increasing the uptake of: passive cooling measures (shading and ventilation); measures to reduce indoor moisture; improved air quality and water efficiency; and, in homes at risk of flooding, the installation of property-level flood protection.

We cannot meet our climate objectives without a major improvement in UK housing.

Housing crisis

New figures that reveal the true scale of the housing crisis in England for the first time have been published by the National Housing Federation and Crisis, the national charity for homeless people.

The research, conducted by Heriot-Watt University shows that England’s total housing need backlog has reached four million homes.

To both meet this backlog and provide for future demand, the country needs to build 340,000 homes per year until 2031.

The quality of these existing and new homes has an important role in safeguarding people’s health and wellbeing, and in addressing climate change.

In summary

We will not meet our targets for emissions reduction without near complete decarbonisation of the housing stock. Energy use in homes accounts for about 14% of UK greenhouse gas emissions.

These emissions need to fall by at least 24% by 2030 from 1990 levels, but are currently off track. In 2017, annual temperature-adjusted emissions from buildings rose by around 1% relative to the previous year.

Whether or not social housing builders will be able to achieve this whilst simultaneously navigating the materials shortage and challenges posed in a post-pandemic world remains to be seen, but I consider myself an optimist and often marvel at what we achieve as an industry when we work together.

Watch this space!

Joe Bradbury is Digital Editor of Housing Association magazine