Organisations are under increasing pressure from regulators and from their customers to ensure that their buildings and operations use energy in the most sustainable way. According to a survey by the Carbon Trust, published in November, for instance, more than half of consumers (56% said that they would feel more positive about a company that has reduced the carbon footprint of its products.

Next April, another significant piece of environmental legislation comes into force. The Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES) will apply to landlords or tenants of commercial buildings and commercial apartments. Initially, it will prevent new lettings and lease renewals of energy inefficient buildings, in other words, those with F & G ratings. Such buildings are still very common and they house organisations in all sectors around the country. From April 2023, regulations will become tougher still as MEES is extended to all existing leases.

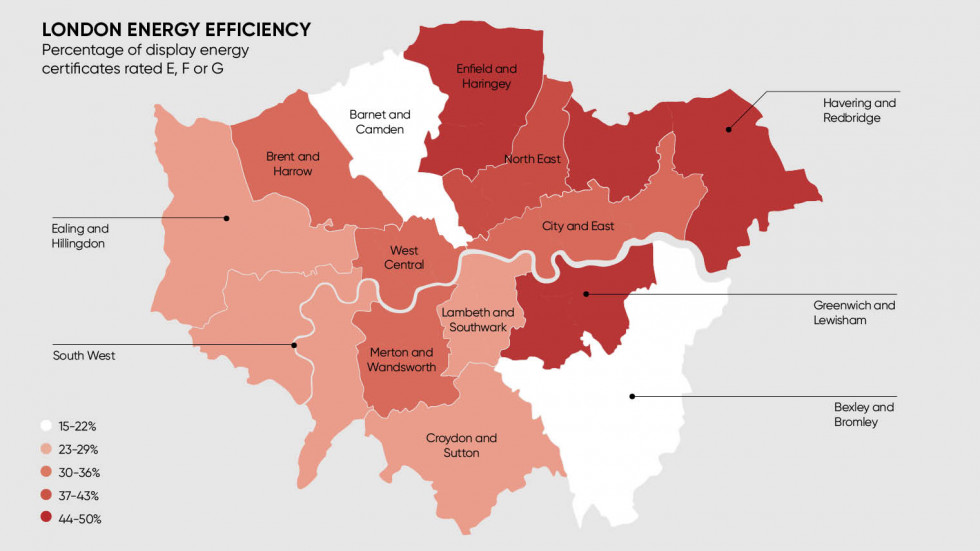

“This is a wake up call to all business leaders and facilities managers,” says Deane Flint, joint managing director at Mitsubishi Electric. He points to findings by the Association for the Conservation of Energy (ACE), which show that in London alone, over a third of commercial buildings have the worst Environmental Energy Performance Certificates (EPC) ratings in the UK, with 18,000 of these only qualifying for an EPC rating of F or G. Of the capital’s 265,000 commercial buildings only 34 per cent have a performance rating of C or above.

Shrewd business leaders are starting to regard legislation not as a problem or threat but as an opportunity.

The ACE report reveals that although commercial and industrial buildings constitute around a quarter of London’s building space they consume almost half the energy, while workplaces are currently responsible for around 42% of the city’s carbon emissions. The report also discovered a similar state of affairs with London’s housing stock where a quarter, that is 830,000 homes, have the worst energy efficiency ratings of E, F or G.

“These figures show that the impact on the commercial property market is likely to be highly significant and they highlight the sheer scale of the challenge facing many building owners and operators,” says Mr Flint. “Failure to comply with the new standards could bring about serious financial repercussions and prevent landlords from letting property until they’ve taken action to meet all these new requirements.”

The MEES regulations come on top of the F-Gas regulations, which came into force in January 2015 and relate to the mixture of gases within an air conditioning system and the possibility of reducing their global warming potential (GWP). The aim of these initiatives and a raft of other new regulations is to ensure that emissions from homes and commercial properties are completely removed by 2050 so that the UK can meet its stringent international targets.

“These new and increasingly onerous requirements will obviously present serious challenges for many organisations,” says Mr Flint. “However, we’ve noticed that a growing number of shrewd business leaders and forward-thinking professionals who develop and manage buildings are starting to regard MEES, F-Gas and other requirements not as a problem or threat but as an opportunity.”

According to the ACE report, for instance, shops that reduce their energy costs by 20% can benefit from the equivalent of a 5% increase in sales. Forward-thinking companies are taking a positive, proactive approach. They’re making the most of government backed renewable technology, such as heat pumps through the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI), which pays for every kilowatt of renewable heat that a system produces, for instance.

Taking a common sense approach

As well as helping companies around the world to find new and effective ways by which to improve the energy rating of their buildings Mitsubishi Electric has been doing the same with its own headquarters over the last eight years.

It has installed an air conditioning system that allows it to cool and heat different parts of the building at the same time as heat rejected from the server room is used to warm other parts of the building. When the gas boiler began to reach the end of its life, rather than replace it the building managers made a case for removing gas from the site altogether and adding a heat pump boiler to the air conditioning system so that rejected heat energy supplies hot water for the kitchens. Photovoltaic cells on the roof supply the building with electricity and sell any excess back to the grid. As a result, the building’s energy rating has now improved from E to B.

“What we’ve done has been relatively simple and straightforward,” says Flint. “We’ve used technology and common sense to build a compelling business case and we’ve saved money and engaged staff in these issues as a result. It’s something that any sensible business can achieve if its leaders are willing to taking action early to meet these new environmental regulations.”

Mitsubishi Electric has produced a free, CPD-accredited guide to MEES or Minimum Energy Efficiency Standard, the legislation demanding that a commercial property in England and Wales is brought up to a minimum EPC (Energy Performance Certificate) rating of ‘E’.

This post by Simon Brooke appeared in a special Times supplement called The Future of Construction that can also be viewed online.

If you have any questions about this article or want to know more, please email us. We will contact the author and will get back to you as soon as we can.